By Sam Jack, sjack@newtonplks.org

NOTE TO READERS: This article first appeared in the April 2020 issue of East Wichita News and WestSide Story. To research it, I used a database of historic newspapers from the Kansas State Historical Society – readily accessible from home. Stay tuned for a video where I’ll explain how you can do your own history exploration using free tools. – Sam

On Tuesday, Oct. 8, 1918, the front page of the Wichita Beacon blared: “NO ARMISTICE SAYS PRESIDENT.”

The end of World War I was coming into view. Kaiser Wilhelm II was to abdicate on Nov. 9, and Germany was to sign an armistice on Nov. 11. A month prior to those big events, more than a dozen front-page Beacon headlines reflected the public’s ongoing preoccupation with the closing acts of the Great War.

Just one small report, in the lower left corner of the Beacon’s front page, touched on the 1918 flu pandemic, also known as the “Spanish Flu” – which would soon become the single deadliest public health disaster in American history.

The Beacon reported that Spanish Flu had “seized” Arkansas City, with more than 70 cases reported in the city in 24 hours. Both Hutchinson and Arkansas City had already shut down schools and public gathering places by Oct. 8.

Despite those ominous reports, and despite the Oct. 5 opening of the temporary Red Cross Flu Hospital in Wichita’s WMTA Building, the Oct. 8 issue of the Beacon gave plenty of space to a “Wichita physician” who wrote that people were getting “unnecessarily alarmed” over “nothing more nor less than a severe cold.”

“This trouble has been present every fall and winter and will be here again next fall and if it has no new appellation there will be no alarm about it,” the anonymous physician wrote. “Avoid drafts and sudden cooling of the body when heated and warm and your chances of getting the Spanish Flu will be very slight.”

Events quickly showed that the doctor was wrong to downplay the 1918 flu. Nearly 700,000 people in the U.S. died of the disease, including 12,000 Kansans.

Diving into 10 days’ worth of newspaper reports on “The Grippe” shows how quickly the crisis escalated in Wichita, inviting comparisons between then and now.

Oct. 9

The Wichita Eagle reports the Red Cross hospital “now fully prepared to take care of 50 patients.” Twenty-seven flu sufferers are in the hospital, including 12 men from a soldiers’ camp at Fairmount College.

The local Red Cross offers free cloth face masks to those caring for flu sufferers at home, with hundreds of women reporting to work rooms and volunteering to sew them. Military forts and installations in Kansas and Missouri press the Red Cross to fabricate and deliver thousands of masks, making it difficult to keep a supply available locally.

Oct. 10

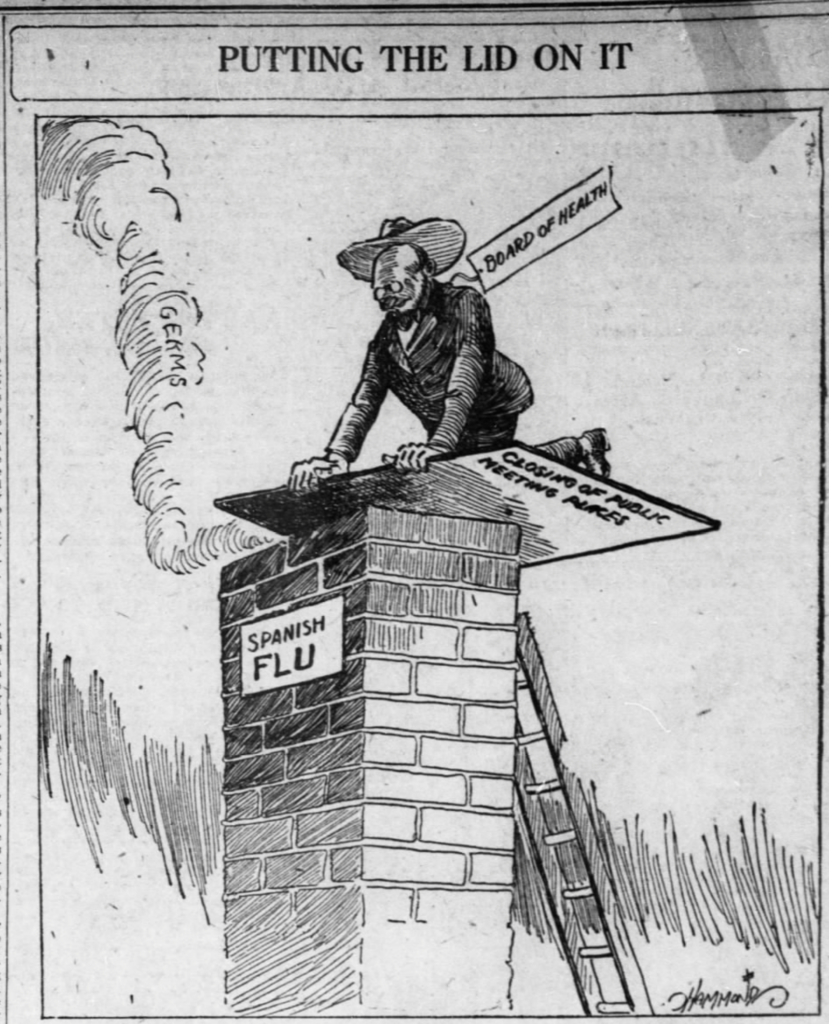

City physician Thomas J. Carter orders the closing of all theaters, schools, and public gathering places in Wichita.

The biggest immediate effect of the order is the premature closing of the Wichita Fall Fair. The fair’s organizers reluctantly confront a large financial loss and haggle with exhibitors over reduced payments. Workers tear down exhibits and hastily pack up booths.

Automobile races, thought to be less risky because they are held outdoors in the fresh air, get permission to go forward, but are rained out anyway.

Wichita suffers its first two influenza deaths on Oct. 10, one at the temporary hospital and one at a private home.

The terms of the “general closing orders” going into effect in Wichita-area cities sound pretty familiar today: no bowling alleys, no skating rinks, no dance halls or theaters.

“Take every possible precaution to prevent exposure to, and the spread of this very contagious disease,” writes Charles L. King, the mayor of El Dorado. “If each person will carefully obey the spirit as well as the words of this order, we will sooner be free of this epidemic.”

Just below Mayor King’s message in the Walnut Valley Times, a piece attributed to “Ahern” captures the public’s state of mind as cases increased and the pandemic takes hold locally.

“This morning I woke up an hour late, and my first thought was – ‘I wonder if that’s a symptom of Spanish Flu!’ The toothpaste didn’t taste right – Spanish Flu! The bath soap burned my eyes – Spanish Flu! … On the way to work I heard coughs and sneezes of other people – Spanish Flu! I felt like coughing and sneezing – Spanish Flu!”

Oct. 11

Forty patients are being treated at the temporary hospital in Wichita, up 13 from two days earlier. “Great difficulty was experienced” in getting workmen to come to the hospital to work on plumbing, electricity, carpentry and cleaning, the Eagle reports, but “others showed loyalty and real devotion to suffering humanity.”

Sedgwick County Red Cross leader Henry Wallenstein says he believes the temporary hospital “has possibly saved the city a thousand cases,” since “all the 40 patients were taken from hotels and boarding places, where large numbers of people congregate.”

The Wichita Public Library closes at 9 p.m., after Dr. Samuel Crumbine, secretary of the state board of health, calls Dr. Thomas Carter, Wichita’s city physician and urges the step. Crumbine informs Carter that libraries in “all other” Kansas cities have already been closed.

By Oct. 11, only two courthouse employees and two sheriff’s deputies do not have the flu. Visitation at the jail is suspended.

Oct. 12

The Sedgwick County Red Cross declares Oct. 12 “Sacrifice Day,” and asks everyone in Wichita “to sacrifice something so that the Red Cross may more efficiently help in the work of stamping out influenza. … Every man and woman in Wichita tonight will probably be wearing a tag showing they have helped in this necessary work,” says the Wichita Eagle.

Schoolgirls, some wearing face masks, volunteer to collect donations and distribute the tags. The Eagle reports that two girls dressed as sailors and “danced and sang on the streets as their part in the campaign.”

Forty new patients are admitted to the flu hospital on Oct. 12. Despite the influx, five Red Cross nurses are transferred from Wichita to care for flu patients in Manhattan. A total of 402 flu cases have been reported in Wichita, with 10 deaths.

Oct. 13

Wallenstein issues a stern warning that Wichita residents should stay home to fight the spread of the flu.

“Wage earners in homes where there is contagion, may come and go, provided they do not come in contact with the patient and if the patient is isolated in a room of the home,” the Eagle reports. “Children must not leave the premises. It was reported that several persons who had a mild attack of influenza were on the streets of the city yesterday.”

Reflecting the inaccurate medical wisdom of the time, Wichita churches hold Sunday Masses and services outdoors on church lawns. “Fresh air” and room to spread out mean outdoor services are less dangerous, but they still bring people into close proximity and, no doubt, contribute to the spread of the flu. After worship, members of Protestant churches stay and socialize all day, the Eagle notes.

Oct. 14

Five days after the Eagle reported that the Red Cross Hospital was “fully prepared to take care of 50,” the paper reports that the hospital now houses about 100 flu patients.

That number does not include all severe flu patients, only those “who live in hotels, rooming houses or other places they could not be properly treated,” the Eagle writes.

Wallenstein again urges the public to keep their children at home. “Avoid public drinking cups, crowded street cars, place the handkerchief before the nose when sneezing, avoid the breath of another person and live in the open air as much as possible.”

More than 200 new cases of influenza are reported in Wichita on Oct. 14. Statewide, more than 3,000 new cases are reported.

Oct. 15

“Unless conditions prevailing in this locality…improve, stores, factories, and other industries will be closed, the city will be districted and placed in charge of civilians who will compel the people to remain in their homes, no one will be permitted to enter or leave the city, and it will be placed under a strict quarantine,” Wallenstein tells the Eagle. “Not only poor, uneducated and unsanitary persons, but also some of the well-to-do, enlightened and finest people in the city are lax in taking the necessary precautions to help swat this epidemic.”

Wichita city manager Louis R. Ash complains that people are coming downtown to “idle” and congregate in front of bulletin boards.

“People should stay at home unless necessity compels them to come down town,” he says. “I think it advisable that the police department scatter these crowds. The sidewalk should be cleared. Too many people come down town just to be coming.”

Oct. 16

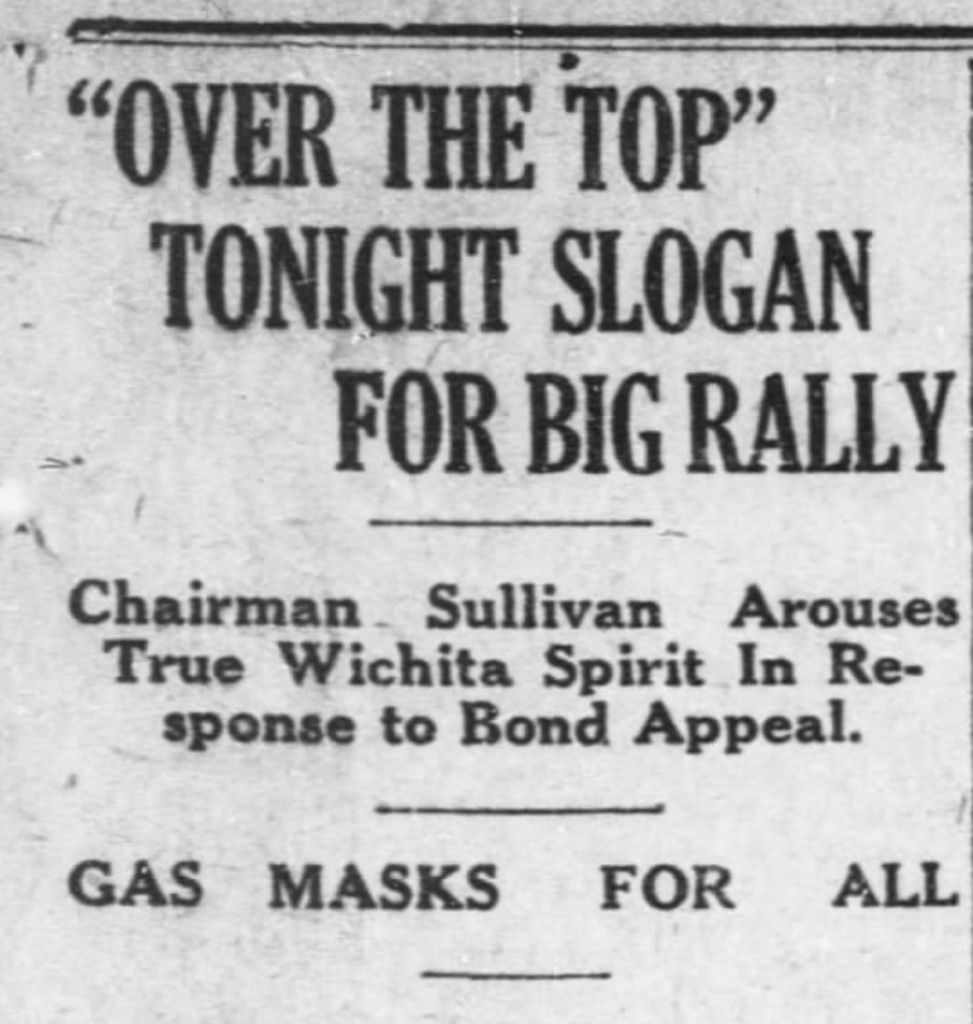

Despite the epidemic, a boxed front-page item in the Oct. 16 Eagle urges Wichitans to take part in a mass meeting in support of Liberty Bonds.

The bonds, used to fund Allied war efforts, are being incessantly promoted in the papers. On the editorial page, “Buy Liberty Bonds” is printed in small type between paragraphs. People who refuse to buy bonds, or to buy “enough” of them, are cast as unpatriotic or even seditious.

“Influenza masks will be given each one who attends so that there will be no danger of infection,” the item states. “The boys at the front, when the word comes, don their masks and go over the top. Surely with our masks on we will go over the top also and make good as they are, for America and for Wichita. … WICHITA MUST GO OVER.”

In the same day’s paper, the Eagle reports that Wichita health authorities have banned outdoor as well as indoor meetings in the city limits – but the Liberty Bond meeting is exempted, apparently as a necessary part of the war effort.

Four hundred businessmen in face masks assemble in the New Crawford Theatre, on Topeka Street near William, to hear speeches and make their pledges in person. Organizers had hoped to draw 1,000.

Oct. 17

Wallenstein reports a shortage of nurses and nurse aids as the number of patients at the Red Cross Hospital grows to 145.

An 11-year-old girl is found wandering the streets with a high fever.

“Upon being taken to the hospital for treatment, it was found that her parents were also confined there,” the Eagle reports. “In the evening a 5-year-old sister of the child was found on the streets with a high fever and she, too, was taken to the Red Cross Hospital.”

Oct. 18

There are only two trained nurses and “but three or four aides” on duty to tend to 145 patients at the Red Cross Hospital. One physician, Dr. G.H. Shirley, is volunteering at the hospital and has been there day and night for a week, the Eagle reports.

The Eagle notes that the flu has reduced its editorial staff to three, only “one of which is employed in a reportorial capacity.”

The day’s influenza report in the Eagle includes an appeal for foster homes for children whose parents are ill. “These children, having been exposed to the influenza, can not be cared for at the children’s home, because there are 50 cases of flu reported at that institution now, and Mr. Wallenstein asks that families of this city, who can, will make an effort to take at least one or two of such children into their own homes.”

The epidemic continues

October was the peak of the epidemic in Kansas, according to Judith R. Johnson’s “Kansas in the ‘Grippe’: The Spanish Influenza Epidemic of 1918,” published in the Spring 1992 issue of Kansas History.

During the last three months of 1918 and the first three months of 1919, 174,094 cases of influenza were reported in Kansas, out of a population of about 1.7 million.

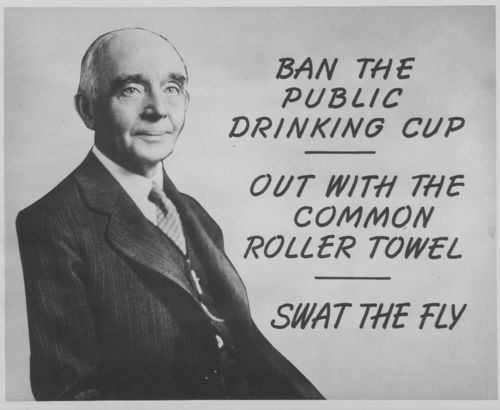

Those numbers meant Kansas got off lightly compared to the U.S. as a whole. At least 25 million Americans, or a quarter of the population, contracted the disease. Johnson praises Dr. Samuel Crumbine, the secretary of the state board of health, for efforts that kept thousands of Kansans safe.

“Crumbine recognized the potential devastation of the impending epidemic, but more importantly, he drew upon his previous experiences when threats to the public health surfaced,” she wrote. “Consequently, Crumbine stressed education as a weapon to fight the flu and launched a statewide program to inform the citizens of ways to prevent the spread of influenza.”

By the end of October, social distancing measures in Kansas were paying off, and Crumbine lifted a statewide order on Nov. 2. Wichita health officials determined that local restrictions would need to remain in place for another week after that.

“According to Dr. Carter, the epidemic is on the increase, and more new cases have been reported during the past two days than at any other time since the epidemic first gained headway in the city,” the Eagle reported Nov. 1.

Later in November, when Kansas health officials started lifting restrictions, they noticed an almost immediate increase in flu cases, according to Johnson. That led to renewed closures and limits on commerce.

In early December, Wichita businessmen won a court ruling that the local health board could not shutter certain industries and activities while allowing others to continue. Health officers immediately met to write a new order that would apply uniformly, across the board. The order limited the number of people who could be in the same place at the same time.

“Clearly recognizing the necessity for restrictions, the owners complied,” Johnson wrote.

In Wichita and across Kansas, most restrictions were lifted by the start of 1919, but frequent local outbreaks continued through March, sickening and killing more people.

In spring 1919, the Kansas state health department estimated the economic cost of the epidemic at more than $100 million, or more than $1.5 billion in today’s dollars.